State of nations: global data privacy policies

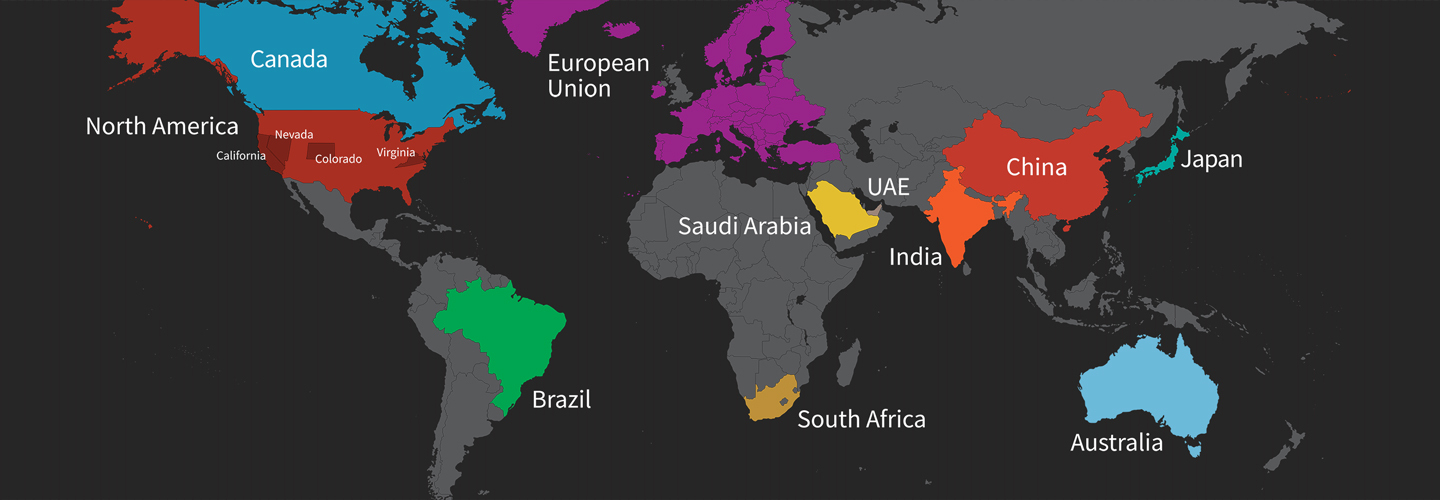

By 2023, it is estimated that 65% of the world's population will have their data covered by some form of privacy regulation (1).

The EU’s GDPR - widely seen as a leader in data privacy legislation - has been increasingly enforced across multiple jurisdictions. Many non-EU countries are now consolidating their data privacy regimes to give their citizens more data rights, ease the transfer of data flows across borders, and help enable further trade.

This article will focus on the newer and bigger players in the field. There are a host of other countries that are working on legislation, these will be added over time as they progress through to actual policy.

The global landscape for data privacy is getting more complex with a variety of approaches by country and state. As a result, some national and global businesses are already adopting the same approach to data privacy across all their markets, regardless of whether specific legislation is in place or not (mostly centred around GDPR compliance as a benchmark).

Notably, some countries have different policies, rationales, and intentions behind their laws; some, like China, have implemented these laws as a way of furthering national interest, some are more focussed on fostering international trade and becoming larger geopolitical actors, while others’ approaches stem from the root need to give increased data rights to citizens with, for example, stringent rules governing data localisation and cross-border transfer.

Click on the country's name below to read about the relating policy:

Australia

The Privacy Act 1988

The data privacy landscape in Australia consists of a mix of federal, state, and territory laws, with the main federal piece of legislation being the Privacy Act 1988. The Act covers the handling of personal information and delegates enforcement power to the Privacy Commissioner.

The Act includes 13 Australian Privacy Principles (APPs). These are principles that govern rights and obligations around how data is collected, used, disclosed, and systems of accountability for “APP entities” - namely private sector bodies, and most government agencies (2).

Australia is also in an ongoing process of updating its data protection regime. In 2019, the Attorney General announced a review of the Act to better protect consumers, with the department inviting submissions for potential changes and considerations until 10 January 2022 (3).

Additionally, in September 2021, the Australian government also published a consultation draft of the Privacy Legislation Amendment (Enhancing Online Privacy and Other Measures) Bill 2021 (Online Privacy Bill) which, if passed, would amend and update the Privacy Act 1988 and bring in changes like increased penalties for breaches, and introduce a framework for a privacy code to be applied to social media and online platforms (4).

South Africa

The Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA) 2013

Whilst the South African Bill of Rights has given citizens a constitutional right to privacy since 1996, the country did not implement specific privacy legislation until 2013 - the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA). Due to the infrastructure and necessary bodies (i.e. the Information Regulator and office bearers) being essentially built from the ground up, there was a sizeable delay between passage and implementation, meaning the POPIA only came into effect in July 2020.

The law creates rights for South African citizens as to how their data is collected and used, and provides legal support to the Bill of Rights existing laws on privacy.

Personal information is widely defined as information relating to an identifiable natural person, and the law is also unique in that it is one of the few data protection laws offering protection to legal entities, i.e. companies and trusts (5).

Previous data breaches in South Africa were rarely reported, but POPIA has meant there is a requirement to report unauthorised access to data to the data subjects and the Information Regulator (the person who monitors activity, investigates, and enforces the POPIA) (6). Failure to comply with the law could cost organisations fines of up to 10 million ZAR (£471,399), as well as lawsuits and criminal penalties of up to ten years (7).

The European Union

The General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) 2018

Passed in 2018, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was the first of its kind, introducing revolutionary changes to the regulation of data handling and processing that would protect EU citizens’ personal data.

At the time of its introduction, GDPR was considered one of the toughest and strictest regulations, often being referred to as the “gold standard” and a reference point for many other comprehensive data protection laws worldwide in countries like Japan and Brazil (8)(9).

The GDPR’s requirements for third-party countries to have adequate levels of protection have also been the foreground to substantial legal change; for example, the Schrems II decision regarding the requirements for cross-border data transfer from the EU to third-party countries.

For more on this legislation, visit our other article: Data privacy in the UK: a legislation breakdown.

India

The Data Protection Bill (PDP) 2019

Home to roughly 1.4 billion people, India is now a major tech hub and has not been shy of large-scale data breach incidents. For example, in May 2021, Air India revealed that they had suffered a data breach, exposing the personal data of roughly 4.5M customers worldwide (10). India had also seen a 37% increase in cyber-attacks in the first quarter of 2020 (compared to 2019) (11). This is particularly important as much of the world’s data is processed and analysed in India, and so a robust system of data protection is essential.

India’s approach to data protection was previously rather fragmented and was covered by numerous different laws, like the Information Technology Act 2000, that ultimately failed to keep up with the pace of technology.

Stemming from the 2017 Puttaswamy vs Union of India case which recognised privacy as a fundamental right in India, the new Data Protection Bill proposes a coherent and comprehensive framework of rules to cover this area (12). The bill imposes restrictions on how data can be processed and used, as well as requirements for data localisation and for companies to appoint data protection officers (13)(14).

In November 2021, a Joint Committee of Parliament (JCP) completed a final report on the Bill (which they named The Data Protection Bill 2021), giving a proposed roadmap for its implementation and enforcement (15). Interestingly, the JCP have also recommended social media companies fall under the remit of the law, which could also potentially make them liable for content on their platforms from unverified accounts (16).

Even though this seems like a step in the right direction for data privacy, some have criticised the bill for its lack of protection against data surveillance, the fact it allows the state to access data, and its shortfalls in the structures of the Data Protection Authority (17).

Brazil

The Brazilian General Data Protection Law (LGPD) 2020

Home to roughly 214 million people, Brazil has the most Internet users in Latin America (18)(19). The Brazilian General Data Protection Law (LGPD) is Brazil's first comprehensive piece of data protection legislation and has been in effect since September 2020, with sanctions becoming enforceable from August 2021.

As with similar comprehensive data protection laws, the legislation holds many similarities to the GDPR in the obligations it sets out, and the principles of data processing it codifies. Some have even suggested the law was partially modelled after GDPR to speed up the process of getting an EU adequacy decision (20).

The LGPD applies to the processing of data by any natural person or legal entity established in Brazil, collecting data in Brazil or processing the data of people in Brazil. The Brazilian Autoridade Nacional de Proteço de Dados (ANPD), Brazil’s data protection authority, is tasked with protecting the personal information of Brazilian data subjects.

Some of the areas exempt from the law include:

Personal data being processed for private or non-economic purposes

Personal data processed for journalistic or academic purposes

Personal data processed for national security, public safety or matters related to criminal proceedings

Anonymised data (data whereby the data subject it applies to is no longer able to be identified) (21)

Maximum fines can be up to 2% of an organisation’s revenue for the previous year and up to a maximum of 50 million reals (about 6.8 million GBP).

China

The Personal Information Protection Law 2021

In August 2021, China passed the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) - the first law of its kind to be passed in the country. The aim of this law was to protect the rights and interests of individuals, regulate personal information processing activities, and facilitate reasonable use of personal information.

As China is a massive data bloc, with heavy use of facial recognition systems, CCTV cameras, and other forms of surveillance, companies have been under increasing pressure regarding how they handle data.

This law came into effect on November 1st 2021 and requires companies to get consent from users before collecting their data, as well as rules for how their data is to be used when it is transferred outside of the country.

This new law, along with the Cybersecurity Law, and the Data Security Law, will form the fabric of China’s data protection and security regime for the foreseeable future.

Some other key new rules in the PIPL are:

The requirement for companies to undergo compliance audits

Consumers can opt-out or request an alternative to having their personal information used for marketing

Consumers can request copies of their personal information, or have it deleted Companies need to take special considerations when designing their interfaces and ensure their infrastructure is appropriate

Data processors need explicit consent from consumers, as opposed to an opt-out system; this consent should be able to be withdrawn easily

If consumers do not consent to their use of personal information, data processors cannot refuse them access to the product or service (unless the processing of data is essential for carrying out the service), removing the “all-or-nothing” approach many processors use

The law is extra-territorial: it applies to those who process personal information of Chinese people both inside China and outside China. Additionally, fines also exceed those of other laws like GDPR - up to 5% of annual revenue or CNY 50 million (£5,916,636). Moreover, where a breach of the PIPL affects a large number of individuals, processors can face both civil and criminal charges (22).

Saudi Arabia

The Personal Data Protection Law (PDPL) 2021

The Saudi Personal Data Protection Law (PDPL) was implemented by Royal Decree in September 2021, becoming effective in March 2022 (23)(24).

According to the announcement by the Saudi Data and AI Authority (SDAIA), the PDPL is intended to ensure the privacy of personal data, regulate data sharing, and prevent the abuse of personal data in line with the goals of the Kingdom’s Vision 2030 to develop a digital infrastructure and support innovation to grow a digital economy (25).

The main features include rights for data subjects, controller registration, controller obligations, data subject consent to processing, purpose limitation, data minimisation, notification in the instance of a data breach (26). It applies to the processing of data by businesses or public entities in Saudi Arabia, and also has an extra-territorial effect, covering the data of Saudi residents from outside the country being processed.

However, the PDPL has tighter restrictions than other countries for transferring data outside of the country: it can only be done if it is necessary to preserve life, combat a disease, satisfy an obligation, and should not prejudice national security, but be limited to what is necessary and proportional and be approved by competent authorities (27).

Unlike other data protection laws, deceased people’s data also falls within the remit of this law, significantly widening the scope of its application in comparison to other laws (28). This stringency puts it more in line with laws like China’s PIPL, as opposed to the GDPR or any US data protection laws.

Moreover, violation of the Saudi law can result in criminal penalties, with some of the highest penalties including punishments like 2 years in prison and SAR 5 million (about £1,000,550) (29).

The United Arab Emirates (UAE)

The Data Protection Law (DLP) 2021

Federal Decree-Law No.45 of 2021 - the Data Protection Law - was announced in the Cabinet in November 2021 and is the first comprehensive data protection law in the UAE (30). Coming into force on January 22nd 2022 and largely mirroring the GDPR, the law is intended to protect the data of all natural people. Among other rights, it gives data subjects the rights of access, amendment, and erasure of their data, as well as emphasising consent for its processing (31).

The law is also extra-territorial, and covers controllers and processors both inside and outside of the UAE who process the personal data of UAE citizens.

Interestingly, government data is exempt from the law; meaning government and judicial bodies do not have to comply with these new requirements on data handling.

The law is also not applicable to personal health-related data and personal banking data, nor to companies and bodies located in free zones (areas in the UAE with separate tax and customs rules and their own frameworks of regulations) which all have their own separate governing laws (32).

The UAE Data Office will also be established under separate legislation to create a new national data privacy regulator, which will create policies surrounding data protection, monitor and address complaints, and provide further guidance on the implementation of the legislation.

With the law now coming into force, bodies covered by its scope have six months from the March 2022 release of executive regulations to ensure they are in compliance (33).

Japan

The Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI)

Data protection in Japan is arguably one of the most active and ever-changing areas of law as over the years, it has continuously been reviewed, changed, and updated (34). The main legislation handling data protection is the Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI), first introduced in 2003. Following numerous data breaches and the consequent 2015 amendment, the APPI has established the Personal Information Protection Commission (PPC) as an independent body that is responsible for protecting the personal information of Japanese citizens.

Under the APPI, before a personal information collector (PIC) processes data, they are required to notify data subjects on the purpose of the processing and prohibited from using the data in any other way without consent (unless certain exemptions apply) (35). Since the law’s passing, Japan has also introduced several regulations and supporting documents to give further clarity and guidance on cross-border data transfer, rules on notification of breach, and the requirements for creating pseudonymous information (36).

Keeping up with the trend of continuous evolution, the Japanese legislature passed the Amended Act on Protection of Personal Information in June 2020, and it is due to come into effect from April 2022. Some of the changes from this amendment will include subjects needing to opt-in to their personal data being transferred outside of Japan. Businesses must also give clear written information on the details of their cross-border transfers including where data is being transferred, the protection systems in place in that country, and further protection methods they plan to take (37).

The United States of America

Due to the constitutional structure of government in the US, power is held at both the federal and the state level, and so individual states are given a lot of discretion in creating, implementing, and enforcing their own legal frameworks.

Considering both this, as well as the size of the United States, legislation regulating data protection and security is approached from both a federal and state level, with no existing singular and comprehensive federal law for the protection of data.

In turn, over the past few years, states have taken initiative in writing and passing their own data protection laws applicable to all those within the territory and those outside who process the data of state residents. However, the US does have some sector-specific federal laws governing data protection in areas like health and finance.

The Senate is also currently in the process of introducing a federal-level data protection law to regulate data handling and protection across the United States (38)(39). With many Americans’ daily activities being pushed online during the covid-19 pandemic, there has been a renewed enthusiasm to create and implement national legislation to ensure all Americans are afforded the protection of their data. Additionally, there have been problems presented by the state-by-state approach to data management; for example, rules regulating autonomous cars have been enacted by a handful of states, but with no federal-level framework, these laws become problematic when vehicles cross state lines. Hence, moves towards federal regulatory frameworks are encouraged.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) 1996

HIPAA governs how personal health-related information is shared and used by healthcare providers, and relevant third parties. The law seeks to ensure “protected health information” (PHI) is not compromised or shared with unauthorised parties.

It applies to “covered entities”, such as health insurance companies, hospitals, and relevant third parties which handle PHI. It also lays a provision for three main rules for privacy, security, and breach notification.

A more detailed explanation of HIPAA can be found here.

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) 1999

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), or the Financial Modernization Act of 1999, imposes responsibilities on financial institutions - banks, mortgage brokers, companies who offer advice on loans, investment, insurance, etc. - to explain how they keep and share their customer’s information, as well as ensure their sensitive data is protected (40). These bodies are required to inform their customers of how their data is shared, communicate their right to opt-out of their data being shared with third parties, as well as ensure specific protections are cemented in their practices (41).

The thrust of this law is to ensure confidentiality and security, so that “non-public information” including credit history, credit card numbers, social security numbers, and addresses are secured. As per the Safeguards Rule, further regulations issued in 2002 by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) (the main antitrust and consumer protection agency) as part of the implementation of the GLBA, financial institutions must have written information security plans which explain how they protect customer information, taking into consideration the size and complexity of the business. It also emphasises properly training and equipping employees with knowledge of the correct procedures and information.

California

The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) 2018

Passed in 2018, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) was the first major piece of comprehensive data privacy legislation passed by an individual state, and the catalyst for other states to take similar steps to implement their own state laws.

The law, holding many similarities to the EU’s GDPR, gives consumers the right to request access to their information, have their data deleted, as well as more control over what companies do with their data and the options to opt-out of having it sold. The law applies to businesses serving Californians and those who either:

make at least $25 million in annual revenue,

collect data from at least 50,000 people,

or that collect 50% or more in revenue from selling personal data fall under this category (42).

The law is enforced by the California Attorney General and companies that fail to comply with the law can be sued by private citizens (individual and class-action lawsuits), as well as the state of California. Consumers can recover damages of up to $750 per incident, and civil penalties can go up to $7,500 per intentional violation.

For the full explanation of the CCPA: click here.

The California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) 2020

The California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) is a ballot measure approved by voters in California in November 2020 and takes effect from January 1 2023, becoming fully enforceable from July 2023.

It seeks to update, expand, and amend the 2018 CCPA. It will strengthen the rights of Californians, further tighten business regulations and establish the California Privacy Protection Agency to enforce the act (43).

Virginia

The Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act 2021

The Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act was signed into law in March 2021, with parties having until January 2023 to comply.

This makes Virginia the second US state, following California, to adopt a comprehensive piece of data privacy legislation (44)(45).

The six main rights include rights to access, correct, delete, data portability, rights to opt-out, and a right to appeal whereby businesses must respond to inquiries within 45 days. It also imposes obligations that limit the collection of data and its use, and implement technical safeguards, data processing assessments, and clear privacy policies (46).

The law applies to businesses in Virginia or those who produce goods and services to Virginia residents, and:

control or process personal data of at least 100,000 people per year or

control or process personal data of at least 30,000 people, and derive more than half their yearly revenue from the sale of personal data (47).

Unlike the CCPA, there is no revenue threshold (i.e. a minimum yearly revenue amount required for the law to apply), meaning that even larger businesses will be exempt if they don’t fall within the conditions. As there is no private right of action, enforcement power lies only with the Attorney General; controllers that fail to cure violations within 30 days of being notified can be fined up to $7,500 per violation.

As this legislation does appear to be less onerous than others of its kind, it is fitting that Virginia’s law has also garnered support from the tech industry and large businesses like Amazon and Microsoft (48).

Nevada

The Nevada Privacy Law 2019

In May 2019, Nevada passed Senate Bill 220 which amended the existing 2017 state law regarding website privacy notices, giving consumers the right to opt-out of their personal data being sold (49)(50). From October 2021, additional obligations on “data brokers” were implemented, as well as the option for consumers to opt-out of a broader range of sales of their personal information (51).

The law applies to “operators” of online businesses, services, and websites; namely, those who collect information of consumers in Nevada and engage in activities that involve and are directed towards people in Nevada (52). Unlike the CCPA, Nevada’s law only covers the sale of information collected over a website or online service, as opposed to general sales; moreover, it does not include rights to access and deletion (53).

Colorado

Colorado Privacy Act 2021

Colorado became the third US state to pass comprehensive data protection legislation, following California and Virginia.

The Colorado Privacy Act (CPA) was enacted in July 2021 and will take effect from 1st July 2023. Like its predecessors in Virginia and California, it has similar requirements regarding consumer rights with some features that differentiate it; i.e. a 60 day cure period where controllers can correct problems before facing penalties.

The law applies to “controllers” that conduct business or offer goods and services to residents of Colorado and control or process data of over 100,000 residents per year or derive revenue from selling personal data of at least 25,000 residents, and unlike California, there is no revenue threshold.

The law covers rights of portability, correction, access, and rights to opt-out of having data sold, and targeted advertising, and residents of Colorado have the right to appeal a controller’s determination if they feel their rights are not being respected (54).

It also codifies the requirement for Data Protection Assessments that should be done before “high risk” processing activities, including processing sensitive data relating to private data like genetic, health, racial, biometric data. Sales of personal data will also require a DPA.

Costs for violations can go up to a hefty $20,000 per violation, but there is no right of action for private individuals, lessening the chance for class action lawsuits and leaving responsibility for enforcement in the hands of the Attorney General (55).

Across the rest of the United States, there are currently active bills going through the legislative process in New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Ohio, and Minnesota (56).

Canada

The federal data privacy regime in Canada is predominantly governed by two laws, namely:

The Privacy Act 1985 which handles government handling of personal data, and

The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) 2000 which covers business handling of personal data

The Privacy Act 1985

The Privacy Act regulates how federal government bodies collect, use, and disclose personal information. The Act governs how the Canadian government can handle data in the course of providing services such as employment insurance, tax matters, pensions, border security, and policing (57). The Act also establishes the role of the Canadian Privacy Commissioner who is in charge of overseeing and supervising the enforcement of the Act, by investigating breaches and seeking rectification. Under the law, Canadians are also enabled to request and access any personal information about themselves controlled by federal institutions.

“Personal information” under the Privacy Act includes any recorded information about an identifiable individual including factors like race, education, medical history, personal opinions, and correspondence sent to a government institution (58). However, there are some exemptions, including information relating to individuals who are federal employees or performing contractual services for government institutions.

Notably, the Privacy Act does not apply to political parties, members of parliament and senators, private sector organisations, and courts.

Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) 2000

The PIPEDA has the primary aim of supporting electronic commerce by protecting how personal information is used, collected, and disclosed by private sector bodies (59). It applies to private organisations that collect and use personal information in the course of commercial activity (60). The law also applies to bodies that are federally regulated, i.e. airports, banks, telecommunication companies (61).

Under the Act, personal information includes any factual or subjective information about identifiable individuals, including direct identifiers like names and age, opinions, medical records, ID numbers, cookie data, and credit records (62).

Companies under PIPEDA’s remit are also bound by the 10 fair information principles to protect personal information, including:

Identifying purposes

Consent

Limiting collection

Accuracy

Safeguards

Openness

Challenging compliance

Accountability

Individual Access

Limiting use, collection, and disclosure (63).

Other provinces like Quebec, Alberta, and British Columbia are also empowered to maintain their own provincial laws regulating how private sector bodies collect and use information. Under the law, all private organisations operating in Canada and that handle personal information crossing provincial or national borders are subject to PIPEDA.

Some exempt areas include personal information handled by federal government organisations covered by the Privacy Act, individuals’ use of personal information for strictly personal reasons, and organisations’ use of personal information solely for journalistic or artistic purposes. Moreover, non-profits and political parties are not covered by PIPEDA.

Notably, in November 2020, Canadian legislators introduced Bill C-11 which seeks to replace and update the PIPEDA. This change would create a new Consumer Privacy Protection Act (CPPA) and a Personal Information and Data Protection Tribunal Act (64). These changes would modernise the current data protection regime and put Canada more in line with data blocs like the EU, and California. Though the bill is still going through the legislative process, we may see significant progress later in 2022.

Further reading and useful links:

https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/new-privacy-laws-from-coast-to-coast-1263737/

https://iclg.com/practice-areas/data-protection-laws-and-regulations/usa

https://iapp.org/media/pdf/resource_center/global_comprehensive_privacy_law_mapping.pdf

References:

https://www.ag.gov.au/rights-and-protections/privacy#:~:text=The%20Privacy%20Act%201988%20

https://iapp.org/news/a/after-a-7-year-wait-south-africas-data-protection-act-enters-into-force/

https://www.dlapiperdataprotection.com/index.html?t=breach-notification&c=ZA

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/22/business/facebook-privacy-law-grandmother.html

https://www.leadersleague.com/en/news/with-the-gdpr-europe-shows-the-world-the-way

https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/the-issues-around-data-localisation/article30906488.ece

https://portswigger.net/daily-swig/indian-authorities-set-to-tighten-data-breach-laws-in-2022

https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/the-issues-around-data-localisation/article30906488.ece

https://www.zdnet.com/article/brazil-to-shift-government-sites-to-single-domain/

https://www.statista.com/topics/2432/internet-usage-in-latin-america/#dossierKeyfigures

https://www.dataguidance.com/sites/default/files/gdpr_lgpd_report.pdf

https://www.clydeco.com/en/insights/2021/09/saudi-arabia-issues-personal-data-protection-law

https://www.natlawreview.com/article/updates-to-saudi-arabia-s-data-protection-law

https://www.clydeco.com/en/insights/2021/09/saudi-arabia-issues-personal-data-protection-law

https://www.clydeco.com/en/insights/2021/09/saudi-arabia-issues-personal-data-protection-law

https://www.natlawreview.com/article/updates-to-saudi-arabia-s-data-protection-law

https://www.natlawreview.com/article/updates-to-saudi-arabia-s-data-protection-law

https://www.clydeco.com/en/insights/2021/11/uae-issues-landmark-personal-data-protection-law

https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/news/uae-data-protection-law

https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/news/uae-data-protection-law

https://www.dataguidance.com/notes/japan-data-protection-overview

https://www.dataguidance.com/notes/japan-data-protection-overview

https://www.commerce.senate.gov/2021/7/wicker-blackburn-introduce-federal-data-privacy-legislation

https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/privacy-and-security/gramm-leach-bliley-act

https://iapp.org/news/a/virginia-passes-the-consumer-data-protection-act/

https://iapp.org/news/a/virginia-passes-the-consumer-data-protection-act/

https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/new-privacy-laws-from-coast-to-coast-1263737/

https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/virginia-s-new-data-privacy-law-an-8812636/

https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/nevada-expands-online-privacy-law-goes-8879325/

https://www.mofo.com/resources/insights/190604-nevada-privacy-law.html

https://iapp.org/resources/article/us-state-privacy-legislation-tracker/

https://www.priv.gc.ca/en/privacy-topics/privacy-laws-in-canada/the-privacy-act/pa_brief/

https://www.priv.gc.ca/en/privacy-topics/privacy-laws-in-canada/the-privacy-act/pa_brief/

https://hyperproof.io/personal-information-protection-electronic-documents-act/

https://parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/43-2/bill/C-11/first-reading#ID0EGBA