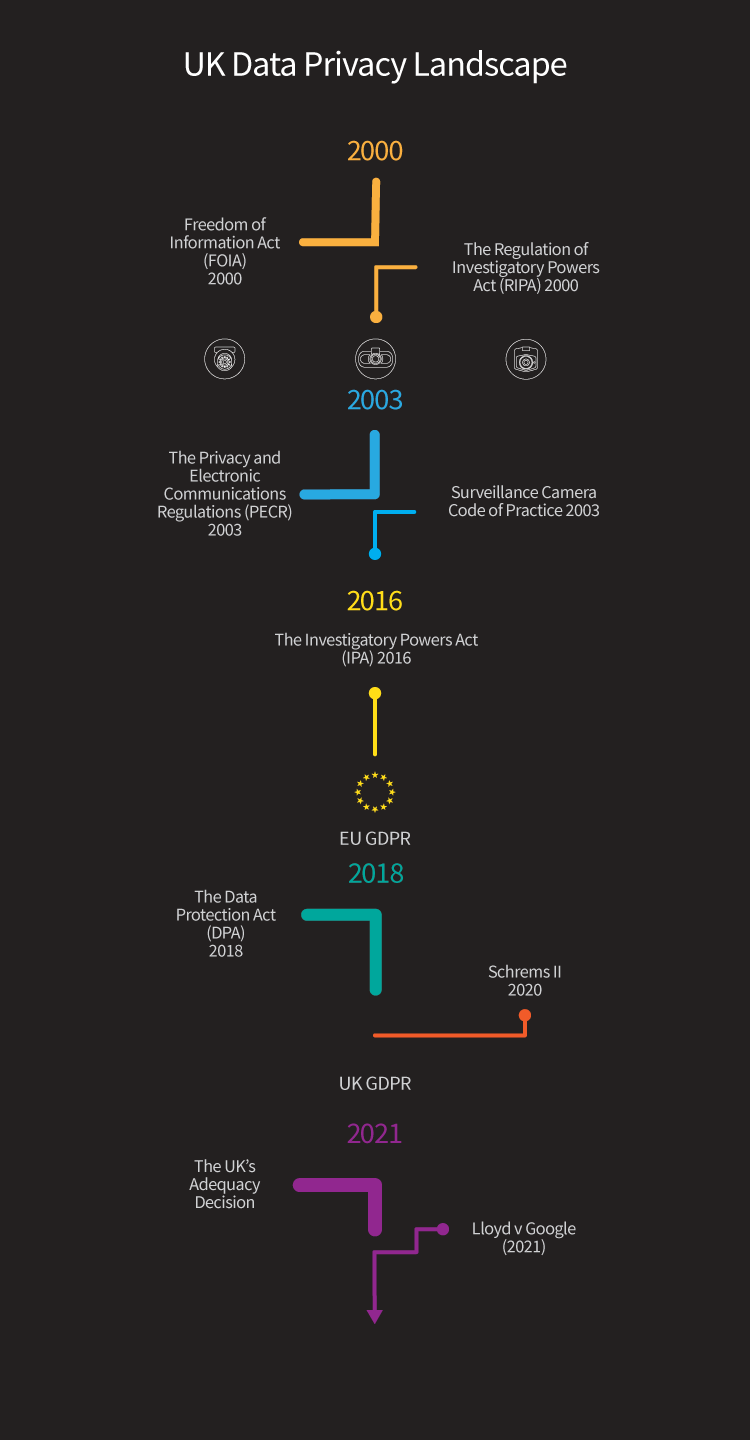

Data privacy in the UK: a legislation breakdown

Navigating the data protection landscape can be complicated - here’s an up-to-date overview of the current data regime in the UK. Click on the legislation names in the image below to skip to full descriptions further down the page:

Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) 2000

The purpose of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) is to increase the transparency of public bodies and to improve accountability within governmental organisations.

Whilst the GDPR and DPA covers individuals’ privacy, the FOIA relates to public information and removes unnecessary secrecy (1).

The FOIA applies to recorded information held by public authorities across the UK - documents, computer files, video footage, emails, etc. It means that public bodies - parliament, local authorities, the NHS, state schools, and the police - have to release information upon request and publish certain information proactively (2). FOI requests are not limited to residents and citizens of the UK, but can also be made by organisations as well as employees of public authorities.

The Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) 2000

Before 2016, The Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) 2000 was the main piece of legislation governing:

different forms of covert surveillance.

The Investigatory Powers Act 2016 (IPA) took over this responsibility, but parts of RIPA are still relevant today and continue to apply.

For example, part 2 of RIPA regulates public authorities’ use of CCTV.

Whilst the use of overt camera systems like CCTV and body-worn cameras for general observational duties do not normally require authorisation, the public should nevertheless be made aware that these systems of surveillance are in use.

Moreover, part 2 of the Protection of Freedoms Act (POFA) 2012 - an act which added to and further clarified previous rules relating to surveillance, use of biometric data, and data protection - amends RIPA so that designated public authorities are required to obtain approval from a magistrate for any covert human intelligence and direct surveillance authorised under RIPA (3).

The Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations (PECR) 2003

The Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations (PECR) 2003 enacts the EU’s 2002 ePrivacy Directive 2002/58/EC - also known as the “cookie law” - and sets out rules on:

Electronic communications, including marketing emails, calls, texts, etc.

The use of cookies

The security of public electronic communication services.

The privacy of traffic and location data (4, 5).

The PECR works alongside the DPA 2018 and the UK GDPR in requiring consent from users for use of cookies and marketing communications across platforms. The ICO can take action against organisations breaching the law with penalties; including criminal prosecution, non-criminal enforcement, and fines of up to £500,000 (6). In 2011, these regulations were amended to include a requirement that websites inform visitors about the cookies used and obtain consent before setting more cookies (7).

Surveillance Camera Code of Practice 2003

S.30 of The Protection of Freedoms Act 2012, which further clarified and expanded on surveillance rules, ushered in the new surveillance camera code in June 2013, along with the appointment of a Surveillance Camera Commissioner, to promote the code and review its operation and impact (8). This code is designed to work alongside the Data Protection Act 2018, as a means to:

regulate the management of personal data of publicly owned surveillance cameras across England and Wales, held by “relevant authorities” -such as police forces and local councils (9).

The code outlines 12 guiding principles which aim to strike a balance between protecting the personal data of individuals and upholding civil liberties. These include cameras being used for specific purposes, for a legitimate aim, in a transparent manner, with accountability, with safeguards from unauthorised use, and with consideration of the effect on individuals and their privacy (10).

It covers the use of camera-related surveillance equipment, including: Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR), body-worn video (BWV), unmanned aerial systems (UAS), and other systems that capture information of identifiable individuals or information relating to individuals.

The Investigatory Powers Act 2016 (IPA) 2016

The IPA is arguably one of the most wide-ranging and sweeping pieces of surveillance legislation in the UK and is:

the primary legal basis for electronic surveillance powers.

It builds on the RIPA, but has more expansive powers to regulate covert surveillance - including equipment interference (i.e. bugging), interception, tracking of electronic communications, and bulk retention of communication data.

The IPA also covers surveillance by authorities and private organisations that involve CCTV cameras.

It provides an outline for the different kinds of interception warrants that can be attained by public authorities and intelligence agencies, including:

Interception warrants

Equipment interference

Bulk communications data acquisition warrants

One of the primary aims of this law is to prohibit the interception of communications without a lawful basis. It applies to UK law enforcement, security, and intelligence bodies; creating additional safeguards and enforcing a regime of wider oversight for these decisions.

The law permits the Secretary of State to issue “technical capability notices” and data retention notices which allow tele-operators to intercept and collect metadata (11). This means authorities can request data - including browsing history for up to 12 months - from these service providers to hack, decrypt, and retain if intelligence officials make a request (12).

A new addition to this law from previous surveillance legislation is the “double-lock” mechanism for more intrusive methods of interception and interference; whereby warrants need to be signed off by both the Home Secretary and a Judicial Commissioner (a senior-level judge) with necessity and proportionality involved (13).

EU GDPR

Passed in 2018, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was the first of its kind; inspiring other national data protection legislative frameworks across the world.

It introduced sweeping changes to the regulation of data handling and processing that would protect EU citizens’ personal data (defined as information relating to an identifiable natural person either directly or indirectly)(14).

It applies to individuals (processing beyond personal or domestic purposes), businesses, and organisations handling personal data. It includes those established in the EU, as well as those outside the EU who offer goods and services and/or monitor the behaviour of individuals in the EU.

GDPR’s main data protection principles are:

Lawfulness, fairness, and transparency

Purpose limitation

Data minimisation

Accuracy

Storage limitation

Integrity and confidentiality (15).

These principles all pertain to how data should be collected and processed, by giving consumers rights of access and consent to their data management; including transparency in how data is used, how long it can be used for, and ensuring limitations on the purposes for which data can be processed.

There is a clear distinction between data that falls within the scope of the GDPR and what falls outside it.

Pseudonymised data is data that cannot be attributed to a specific data subject without the use of additional information (16). While pseudonymisation helps reduce the risk of breach and offers more protection, it is still considered personal data under the GDPR and therefore falls within its remit.

Anonymised data is data that has been rendered anonymous in a way that the data subject is no longer identifiable, so it falls outside the scope of GDPR as it is no longer considered “personal data” (17).

Under GDPR, organisations must report any breaches of personal data to the relevant supervisory authority within 72 hours, and may also need to inform individuals as soon as possible if the breach is significant (18).

Although the UK has left the European Union (and adopted its own version of GDPR), organisations dealing with customers based in the EU must still abide by EU GDPR provisions.

The Data Protection Act (DPA) 2018

The EU gave the member states the right to implement the GDPR into their domestic legislation, permitting them to interpret the law in light of their national frameworks and implement it with the required exemptions and adaptations.

In 2018, The Data Protection Act (DPA) was passed to update the DPA 1998 and implement GDPR into UK law.

Post-Brexit, the DPA remains a part of national law and works alongside the UK GDPR.

The DPA sets out:

separate data protection rules for law enforcement and intelligence services,

extends specific data protection to other areas like national security and defence,

the functions of the ICO (19), and

provides extra safeguards for sensitive data: i.e. information relating to factors including ethnicity, religion, genetic data, and political opinions (20).

At its heart, the act gives people increased rights and control over their data.

It gives people the right to access their personal information and claim damages when they suffer a breach of their personal data. It also allows any requests for personal data to be made through subject access requests (SARs) which must receive a response within 30 days.

UK GDPR

In 2020 following its exit from the European Union, the UK incorporated the EU GDPR into national law, now known as the UK GDPR.

Other than some technical changes, the essence of the regulations remains the same.

The UK GDPR is still based on the key principles of lawfulness, fairness and transparency, purpose and storage limitation, data minimisation, accuracy, security, and accountability. This means that UK data subjects still have the right to access, erase, rectify, and object to their personal data being processed. It also has extra-territorial scope, i.e. it applies to organisations outside the UK that process data and offer services to those in the UK.

However, this is where the UK GDPR differs:

It has a more limited definition of “personal data”,

The age for consent for data processing has changed to 13 instead of 16,

There is no longer a requirement of authority to process criminal data,

The allowing of automated data to be processed, and

The maximum fine for breaches is £17.5 million instead of 20 million euros (21, 22).

The future of the UK GDPR doesn’t seem to be set in stone, with current discussions in the UK government to consider moving away from a “box-ticking” exercise towards a more flexible approach to data sharing (23).

Schrems II

Schrems II is a legal decision made by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in 2020 relating to cross-border data transfers.

When Max Schrems, an Austrian privacy advocate, brought a second challenge to Facebook in front of the CJEU in 2020, he argued that the US did not have adequate protections for data of EU citizens. As a result, the Privacy Shield agreement (which allowed cross-border data transfers between the two blocs) was considered invalid, and new requirements for the use of standard contractual clauses (SCCs) were put in place.

For the full story, read our recent article.

The UK’s Adequacy Decision

In June 2021, the UK received an adequacy decision from the European Commission, declaring that the data protection regime in the UK was satisfactory and met the EU’s standards.

This meant that the UK had adequate legal safeguards in place to protect the privacy rights of data of EU citizens, so cross-border data transfer with EU countries could continue.

However, unlike other adequacy decisions which are permanent, the UK’s decision has a sunset clause and expires after 4 years. As a result, there may be potential changes in the future - depending on whether the UK decides to strip, change, or entirely repeal UK GDPR.

Moreover, as was highlighted in the Schrems II ruling, should the UK maintain a close relationship with third party countries like the US who have large-scale surveillance regimes, this may also undermine the adequacy decision, as the UK would essentially become a “backdoor” to transferring EU citizen’s data to countries with inadequate privacy frameworks.

Lloyd v Google (2021)

Service providers will have breathed a sigh of relief last month after the UK Supreme Court rejected a case against Google for loss of control of personal data. The case, brought by Mr. Richard Lloyd, former director of the consumer rights group Which?, represented 4 million iPhone users and argued that Google had unlawfully processed data via third-party cookies in Safari without consent (24).

In so doing, Lloyd’s counsel argued that Google could bypass privacy settings in order to collect data and use it for advertising purposes. The Supreme Court overturned the previous ruling by the Court of Appeal and unanimously found that claims for unlawful processing of data, as per the Data Protection Act 1998, required proof of material damage (like financial loss or mental distress): i.e. misuse of data in itself does not constitute damage for the purpose of receiving compensation.

They also ruled that such cases would require the damage to all parties involved to be assessed individually; claims for damages could not be brought as representative actions unless there was a common basis for all the members of the class. Had this verdict gone the other way, it could have opened the floodgates to other class-action lawsuits (without individually identifying these members) claiming compensation for loss of control of their personal data (25). However, it is unclear whether this has set an official precedent for how data privacy class actions will be dealt with in the UK in the future.

Further reading and useful links:

https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/guide-to-freedom-of-information/what-is-the-foi-act/#8

https://iapp.org/news/a/what-does-the-schrems-ii-judgement-mean-for-the-uk-and-eu-uk-data-flows/

References:

https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/guide-to-freedom-of-information/what-is-the-foi-act/#8

https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/guide-to-freedom-of-information/what-is-the-foi-act/#8

https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/guide-to-pecr/what-are-pecr/

https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/guide-to-pecr/what-are-pecr/

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2011/1208/introduction/made

S.33 of the POFA 2012

Chapter 2 of the Code of Practice

Metadata describes details about communications, i.e. the duration of calls, email recipients, IP addresses where communications were sent from, etc.

Article 4 of the GDPR

Article 5 of the GDPR

Article 4(5) of the GDPR

Recital 26 of the GDPR

Part 5 and 6 of the DPA 2018

https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/docs/uksc-2019-0213-judgment.pdf